cogitoergosum

2010-04-22 22:57:47 UTC

Proto-Indo-European language: Sid Harth

Proto-Indo-European language

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"PIE" redirects here. For the pastry, see Pie. For other uses, see PIE

(disambiguation).

This article contains characters used to write reconstructed Proto-

Indo-European words. Without proper rendering support, you may see

question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode

characters.

Indo-European topics

Indo-European languages (list) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_languages

Albanian · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albanian_language

Armenian · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armenian_language

Baltic . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baltic_languages

Celtic · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celtic_languages

Germanic · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germanic_languages

Greek . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_language

Indo-Iranian . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Iranian_languages

(Indo-Aryan, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Aryan_languages

Iranian) . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iranian_languages

Italic · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italic_languages

Slavic . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavic_languages

extinct:

Anatolian · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatolian_languages

Paleo-Balkans http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paleo-Balkan_languages

(Dacian, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dacian_language

Phrygian, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phrygian_language

Thracian) · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thracian_language

Tocharian . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tocharian_languages

Indo-European peoples http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_people

Europe:

Balts · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balts

Slavs · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavic_peoples

Albanians · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albanians

Italics · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_peoples_of_Italy

Celts · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celts

Germanic peoples · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germanic_peoples

Greeks · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greeks

Paleo-Balkans

(Illyrians · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illyrians

Thracians · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thracians

Dacians) · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dacians

Asia:

Anatolians . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatolians

(Hittites, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hittites

Luwians) · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luwians

Armenians · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armenians

Indo-Iranians . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Iranians

(Iranians· http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iranian_peoples

Indo-Aryans) · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Aryans

Tocharians . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tocharians

Proto-Indo-Europeans http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-Europeans

Language · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_language

Society · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_society

Religion . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_religion

Urheimat hypotheses http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_Urheimat_hypotheses

Kurgan hypothesis http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurgan_hypothesis

Anatolia · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatolian_hypothesis

Armenia · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armenian_hypothesis

India · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Out_of_India_theory

PCT . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paleolithic_Continuity_Theory

Indo-European studies http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_studies

The Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) is the unattested,

reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, spoken

by the Proto-Indo-Europeans. The existence of such a language has been

accepted by linguists for over a century, and reconstruction is far

advanced and quite detailed.

Scholars estimate that PIE may have been spoken as a single language

(before divergence began) around 4000 BC, though estimates by

different authorities can vary by more than a millennium. The most

popular hypothesis for the origin and spread of the language is the

Kurgan hypothesis, which postulates an origin in the Pontic-Caspian

steppe of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. In modern times the

existence of the language was first postulated in the 18th century by

Sir William Jones, who observed the similarities between Sanskrit,

Ancient Greek, and Latin. By the early 1900s well-defined descriptions

of PIE had been developed that are still accepted today (with some

refinements).

As there is no direct evidence of Proto-Indo-European language, all

knowledge of the language is derived by reconstruction from later

languages using linguistic techniques such as the comparative method

and the method of internal reconstruction. PIE is known to have had a

complex system of morphology that included inflections (adding

prefixes and suffixes to word roots, as is common in Romance

languages), and ablaut (changing vowel sounds in word roots, as is

common in Germanic languages). Nouns used a sophisticated system of

declension and verbs used a similarly sophisticated system of

conjugation.

Relationships to other language families, including the Uralic

languages, have been proposed though all such suggestions remain

controversial.

Discovery and reconstruction

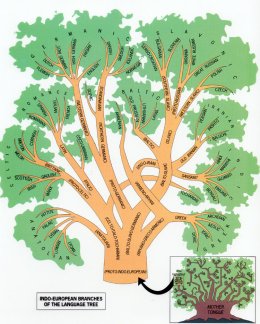

Classification of Indo-European languages. (click to enlarge)

Historical and geographical setting

Main article: Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_Urheimat_hypotheses

There are several competing hypotheses about when and where PIE was

spoken. The Kurgan hypothesis is "the single most popular" model,[1]

[2] postulating that the Kurgan culture of the Pontic steppe were the

hypothesized speakers of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European

language. However, alternative theories such as the Anatolian urheimat

and Armenian hypothesis have also gained acceptance.

The satemization process that resulted in the Centum-Satem isogloss

probably started as early as the fourth millennium BC[3] and the only

thing known for certain is that the proto language must have been

differentiated into unconnected daughter dialects by the late 3rd

millennium BC.

Mainstream linguistic estimates of the time between PIE and the

earliest attested texts (ca. nineteenth century BC; see Kültepe texts)

range around 1,500 to 2,500 years, with extreme proposals diverging up

to another 100% on either side. Other than the aforementioned,

predominant Kurgan hypothesis, proposed models include:

the 4th millennium BC (excluding the Anatolian branch) in Armenia,

according to the Armenian hypothesis (proposed in the context of

Glottalic theory);

the 5th millennium BC (4th excluding the Anatolian branch) in the

Pontic-Caspian steppe, according to the popular Kurgan hypothesis;

the 6th millennium BC or later in Northern Europe according to Lothar

Kilian's and, especially, Marek Zvelebil's models of a broader

homeland;

the 6th millennium BC in India, according to Koenraad Elst's Out of

India model;

the 7th millennium BC in Ariana/BMAC according to a number of

scholars.

the 7th millennium BC in Anatolia (the 5th, in the Balkans, excluding

the Anatolian branch), according to Colin Renfrew's Anatolian

hypothesis;

the 7th millennium BC in Anatolia (6th excluding the Anatolian

branch), according to a 2003 glottochronological study;[4]

before the 10th millennium BC, in the Paleolithic Continuity Theory.

History

Main article: Indo-European studies http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_studies

Indo-European studies began with Sir William Jones making and

propagating the observation that Sanskrit bore a certain resemblance

to classical Greek and Latin. In The Sanscrit Language (1786) he

suggested that all three languages had a common root, and that indeed

they may all be further related, in turn, to Gothic and the Celtic

languages, as well as to Persian.

His third annual discourse before the Asiatic Society on the history

and culture of the Hindus (delivered on 2 February 1786 and published

in 1788) with the famed "philologer" passage is often cited as the

beginning of comparative linguistics and Indo-European studies. This

is Jones' most quoted passage, establishing his tremendous find in the

history of linguistics:

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful

structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin,

and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them

a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of

grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong

indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without

believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps,

no longer exists; there is a similar reason, though not quite so

forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though

blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the

Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family.

This common source came to be known as Proto-Indo-European.

The classical phase of Indo-European comparative linguistics leads

from Franz Bopp's Comparative Grammar (1833) to August Schleicher's

1861 Compendium and up to Karl Brugmann's Grundriss published from the

1880s. Brugmann's junggrammatische re-evaluation of the field and

Ferdinand de Saussure's development of the laryngeal theory may be

considered the beginning of "contemporary" Indo-European studies.

PIE as described in the early 1900s is still generally accepted today;

subsequent work is largely refinement and systematization, as well as

the incorporation of new information, notably the Anatolian and

Tocharian branches unknown in the 19th century.

Notably, the laryngeal theory, in its early forms discussed since the

1880s, became mainstream after Jerzy Kuryłowicz's 1927 discovery of

the survival of at least some of these hypothetical phonemes in

Anatolian. Julius Pokorny's Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

(1959) gave an overview of the lexical knowledge accumulated until the

early 20th century, but neglected contemporary trends of morphology

and phonology, and largely ignored Anatolian and Tocharian.

The generation of Indo-Europeanists active in the last third of the

20th century (such as Calvert Watkins, Jochem Schindler and Helmut

Rix) developed a better understanding of morphology and, in the wake

of Kuryłowicz's 1956 Apophonie, understanding of the ablaut. From the

1960s, knowledge of Anatolian became certain enough to establish its

relationship to PIE; see also Indo-Hittite.

Method

Main articles: Historical linguistics and Indo-European sound laws

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_linguistics

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_sound_laws

There is no direct evidence of PIE, because it was never written. All

PIE sounds and words are reconstructed from later Indo-European

languages using the comparative method and the method of internal

reconstruction. An asterisk is used to mark reconstructed PIE words,

such as *wódr̥ 'water', *ḱwṓn 'dog' (English hound), or *tréyes 'three

(masculine)'. Many of the words in the modern Indo-European languages

seem to have derived from such "protowords" via regular sound changes

(e.g., Grimm's law).

As the Proto-Indo-European language broke up, its sound system

diverged as well, according to various sound laws in the daughter

languages. Notable among these are Grimm's law and Verner's law in

Proto-Germanic, loss of prevocalic *p- in Proto-Celtic, reduction to h

of prevocalic *s- in Proto-Greek, Brugmann's law and Bartholomae's law

in Proto-Indo-Iranian, Grassmann's law independently in both Proto-

Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian, and Winter's law and Hirt's law in Balto-

Slavic.

Relationships to other language families

Proposed genetic connections

Many higher-level relationships between Proto-Indo-European and other

language families have been proposed, but these hypothesized

connections are highly controversial. A proposal often considered to

be the most plausible of these is that of an Indo-Uralic family,

encompassing PIE and Uralic. The evidence usually cited in favor of

this consists in a number of striking morphological and lexical

resemblances. Opponents attribute the lexical resemblances to

borrowing from Indo-European into Uralic. Frederik Kortlandt, while

advocating a connection, concedes that "the gap between Uralic and

Indo-European is huge", while Lyle Campbell, an authority on Uralic,

denies any relationship exists.

Other proposals, further back in time (and proportionately less

accepted), link Indo-European and Uralic with Altaic and the other

language families of northern Eurasia, namely Yukaghir, Korean,

Japanese, Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Nivkh, Ainu, and Eskimo-Aleut, but

excluding Yeniseian (the most comprehensive such proposal is Joseph

Greenberg's Eurasiatic), or link Indo-European, Uralic, and Altaic to

Afro-Asiatic and Dravidian (the traditional form of the Nostratic

hypothesis), and ultimately to a single Proto-Human family.

A more rarely mentioned proposal associates Indo-European with the

Northwest Caucasian languages in a family called Proto-Pontic.

Etruscan shows some similarities to Indo-European. There is no

consensus on whether these are due to a genetic relationship,

borrowing, chance and sound symbolism, or some combination of these.

Proposed areal connections

The existence of certain PIE typological features in Northwest

Caucasian languages may hint at an early Sprachbund[5] or substratum

that reached geographically to the PIE homelands.[6] This same type of

languages, featuring complex verbs and of which the current Northwest

Caucasian languages might have been the sole survivors, was cited by

Peter Schrijver to indicate a local lexical and typological

reminiscence in western Europe pointing to a possible Neolithic

substratum.[7]

Phonology

Main article: Proto-Indo-European phonology

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_phonology

Consonants

Labial Coronal Dorsal Laryngeal

palatal plain labial

Nasal *m *n

Plosive voiceless

*p *t *ḱ *k *kʷ

voiced *b *d *ǵ *g *gʷ

aspirated *bʰ *dʰ *ǵʰ *gʰ *gʷʰ

Fricative *s *h₁, *h₂, *h₃

Liquid *r, *l

Semivowel *y *w

Alternative notations: The aspirated plosives are sometimes written as

*bh, *dh, *ǵh, *gh, *gʷh; for the palatals, *k̑, *g̑ are often used;

and *i̯, *u̯ can replace *y, *w.

The pronunciation of the laryngeals is disputed, at least *h₁ might

not have been a fricative.

Vowels

Short vowels: *e, *o (and possibly *a).

Long vowels: *ē, *ō (and possibly *ā). Sometimes a colon (:) is

employed instead of the macron sign to indicate vowel length (*a:,

*e:, *o:).

Diphthongs: *ei, *eu, *ēi, *ēu, *oi, *ou, *ōi, *ōu, (*ai, *au, *āi,

*āu). Diphthongs are sometimes understood as combinations of a vowel

plus a semivowel, e. g. *ey or *ei̯ instead of *ei.[8]

Vocalic allophones of laryngeals, nasals, liquids and semivowels:

*h̥₁, *h̥₂, *h̥₃, *m̥, *n̥, *l̥, *r̥, *i, *u.

Long variants of these vocalic allophones may have appeared already in

the proto-language by compensatory lengthening (for example of a vowel

plus a laryngeal): *m̥̄, *n̥̄, *l̥̄, *r̥̄, *ī, *ū.

It is often suggested that all *a and *ā were earlier derived from an

*e preceded or followed by *h₂, but Mayrhofer[9] has argued that PIE

did in fact have *a and *ā phonemes independent of h₂.

Morphology

Root

Main article: Proto-Indo-European root http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_root

PIE was an inflected language, in which the grammatical relationships

between words were signaled through inflectional morphemes (usually

endings). The roots of PIE are basic morphemes carrying a lexical

meaning. By addition of suffixes, they form stems, and by addition of

desinences (usually endings), these form grammatically inflected words

(nouns or verbs). PIE roots are understood to be predominantly

monosyllabic with a basic shape CvC(C). This basic root shape is often

altered by ablaut. Roots which appear to be vowel initial are believed

by many scholars to have originally begun with a set of consonants,

later lost in all but the Anatolian branch, called laryngeals (usually

indicated *H, and often specified with a subscript number *h₁, *h₂,

*h₃). Thus a verb form such as the one reflected in Latin agunt, Greek

ἄγουσι (ágousi), Sanskrit ajanti would be reconstructed as *h₂eǵ-onti,

with the element *h₂eǵ- constituting the root per se.

Ablaut

Main article: Indo-European ablaut http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_ablaut

One of the distinctive aspects of PIE was its ablaut sequence that

contrasted the vowel phonemes *o / *e / Ø [no vowel] within the same

root. Ablaut is a form of vowel variation which changed between these

three forms perhaps depending on the adjacent sounds and placement of

stress in the word. These changes are echoed in modern Indo-European

languages where they have come to reflect grammatical categories.

These ablaut grades are usually referred to as: e-grade and o-grade,

sometimes collectively termed full grade; zero-grade (no vowel, Ø);

and lengthened grade (*ē or *ō). Modern English sing, sang, sung is an

example of such an ablaut set and reflects a pre-Proto-Germanic

sequence *sengw-, *songw-, *sngw-. Some scholars believe that the

inflectional affixes of Indo European reflect ablaut variants, usually

zero-grade, of older PIE roots. Often the zero-grade appears where the

word's accent has shifted from the root to one of the affixes. Thus

the alternation found in Latin est, sunt reflects PIE *h₁és-ti, *h₁s-

ónti.

Noun

Main article: Proto-Indo-European noun http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_noun

Proto-Indo-European nouns were declined for eight or nine cases

(nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental, ablative,

locative, vocative, and possibly a directive or allative).[10] There

were three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter.

There are two major types of declension, thematic and athematic.

Thematic nominal stems are formed with a suffix *-o- (in vocative *-e)

and the stem does not undergo ablaut. The athematic stems are more

archaic, and they are classified further by their ablaut behaviour

(acro-dynamic, protero-dynamic, hystero-dynamic and holo-dynamic,

after the positioning of the early PIE accent (dynamis) in the

paradigm).

Pronoun

Main article: Proto-Indo-European pronoun http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_pronoun

PIE pronouns are difficult to reconstruct owing to their variety in

later languages. This is especially the case for demonstrative

pronouns. PIE had personal pronouns in the first and second person,

but not the third person, where demonstratives were used instead. The

personal pronouns had their own unique forms and endings, and some had

two distinct stems; this is most obvious in the first person singular,

where the two stems are still preserved in English I and me. According

to Beekes,[11] there were also two varieties for the accusative,

genitive and dative cases, a stressed and an enclitic form.

Personal pronouns (Beekes)

First person Second person

Singular Plural Singular Plural

Nominative *h₁eǵ(oH/Hom) *wei *tuH *yuH

Accusative *h₁mé, *h₁me *nsmé, *nōs *twé *usmé, *wōs

Genitive *h₁méne, *h₁moi *ns(er)o-, *nos *tewe, *toi *yus(er)o-, *wos

Dative *h₁méǵʰio, *h₁moi *nsmei, *ns *tébʰio, *toi *usmei

Instrumental *h₁moí ? *toí ?

Ablative *h₁med *nsmed *tued *usmed

Locative *h₁moí *nsmi *toí *usmi

As for demonstratives, Beekes tentatively reconstructs a system with

only two pronouns: *so / *seh₂ / *tod "this, that" and *h₁e /

*(h₁)ih₂ / *(h₁)id "the (just named)" (anaphoric). He also postulates

three adverbial particles *ḱi "here", *h₂en "there" and *h₂eu "away,

again", from which demonstratives were constructed in various later

languages.

Verb

Main article: Proto-Indo-European verb http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_verb

The Indo-European verb system is complex and, like the noun, exhibits

a system of ablaut. Verbs have at least four moods (indicative,

imperative, subjunctive and optative, as well as possibly the

injunctive, reconstructible from Vedic Sanskrit), two voices (active

and mediopassive), as well as three persons (first, second and third)

and three numbers (singular, dual and plural). Verbs are conjugated in

at least three "tenses" (present, aorist, and perfect), which actually

have primarily aspectual value. Indicative forms of the imperfect and

(less likely) the pluperfect may have existed. Verbs were also marked

by a highly developed system of participles, one for each combination

of tense and mood, and an assorted array of verbal nouns and

adjectival formations.

Buck[12] Beekes[11]

Athematic Thematic Athematic Thematic

Singular 1st *-mi *-ō *-mi *-oH

2nd *-si *-esi *-si *-eh₁i

3rd *-ti *-eti *-ti *-e

Plural 1st *-mos/mes *-omos/omes *-mes *-omom

2nd *-te *-ete *-th₁e *-eth₁e

3rd *-nti *-onti *-nti *-o

Numbers

Main article: Proto-Indo-European numerals

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_numerals

The Proto-Indo-European numerals are generally reconstructed as

follows:

Sihler[13] Beekes[11]

one *Hoi-no-/*Hoi-wo-/*Hoi-k(ʷ)o-; *sem- *Hoi(H)nos

two *d(u)wo- *duoh₁

three *trei- (full grade) / *tri- (zero grade) *treies

four *kʷetwor- (o-grade) / *kʷetur- (zero grade)

(see also the kʷetwóres rule) *kʷetuōr

five *penkʷe *penkʷe

six *s(w)eḱs; originally perhaps *weḱs *(s)uéks

seven *septm̥ *séptm

eight *oḱtō, *oḱtou or *h₃eḱtō, *h₃eḱtou *h₃eḱteh₃

nine *(h₁)newn̥ *(h₁)néun

ten *deḱm̥(t) *déḱmt

twenty *wīḱm̥t-; originally perhaps *widḱomt- *duidḱmti

thirty *trīḱomt-; originally perhaps *tridḱomt- *trih₂dḱomth₂

forty *kʷetwr̥̄ḱomt-; originally perhaps *kʷetwr̥dḱomt-

*kʷeturdḱomth₂

fifty *penkʷēḱomt-; originally perhaps *penkʷedḱomt- *penkʷedḱomth₂

sixty *s(w)eḱsḱomt-; originally perhaps *weḱsdḱomt- *ueksdḱomth₂

seventy *septm̥̄ḱomt-; originally perhaps *septm̥dḱomt- *septmdḱomth₂

eighty *oḱtō(u)ḱomt-; originally perhaps *h₃eḱto(u)dḱomt-

*h₃eḱth₃dḱomth₂

ninety *(h₁)newn̥̄ḱomt-; originally perhaps *h₁newn̥dḱomt-

*h₁neundḱomth₂

hundred *ḱm̥tom; originally perhaps *dḱm̥tom *dḱmtóm

thousand *ǵheslo-; *tusdḱomti *ǵʰes-l-

Lehmann[14] believes that the numbers greater than ten were

constructed separately in the dialects groups and that *ḱm̥tóm

originally meant "a large number" rather than specifically "one

hundred."

Particle

Main article: Proto-Indo-European particlehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_particle

Many particles could be used both as adverbs and postpositions, like

*upo "under, below". The postpositions became prepositions in most

daughter languages. Other reconstructible particles include negators

(*ne, *mē), conjunctions (*kʷe "and", *wē "or" and others) and an

interjection (*wai!, an expression of woe or agony).

Sample texts

As PIE was spoken by a prehistoric society, no genuine sample texts

are available, but since the 19th century modern scholars have made

various attempts to compose example texts for purposes of

illustration. These texts are educated guesses at best; Calvert

Watkins in 1969 observes that in spite of its 150 years' history,

comparative linguistics is not in the position to reconstruct a single

well-formed sentence in PIE. Nevertheless, such texts do have the

merit of giving an impression of what a coherent utterance in PIE

might have sounded like.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calvert_Watkins

Published PIE sample texts:

Schleicher's fable (Avis akvasas ka) by August Schleicher (1868),

modernized by Hermann Hirt (1939) and Winfred Lehmann and Ladislav

Zgusta (1979)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schleicher%27s_fable

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/August_Schleicher

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann_Hirt

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winfred_Lehmann

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ladislav_Zgusta

The king and the god (rēḱs deiwos-kʷe) by S. K. Sen, E. P. Hamp et al.

(1994)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_king_and_the_god

Notes

^ Mallory (1989:185). "The Kurgan solution is attractive and has been

accepted by many archaeologists and linguists, in part or total. It is

the solution one encounters in the Encyclopaedia Britannica and the

Grand Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Larousse."

^ Strazny (2000:163). "The single most popular proposal is the Pontic

steppes (see the Kurgan hypothesis)..."

^ ".. the satemization process can be dated to the last centuries of

the fourth millennium." [1] THE SPREAD OF THE INDO-EUROPEANS -Frederik

Kortlandt.

^ Russell D. Gray and Quentin D. Atkinson, Language-tree divergence

times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin, Nature 426

(27 November 2003) 435-439

^ [2] Frederik Kortlandt-GENERAL LINGUISTICS AND INDO-EUROPEAN

RECONSTRUCTION, 1993

^ [3] The spread of the Indo-Europeans - Frederik Kortlandt, 1989

^ [4] Peter Schrijver - Keltisch en de buren: 9000 jaar taalcontact,

University of Utrecht, March 2007.

^ Rix, H. Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben (2 ed.).

^ Mayrhofer 1986: 170 ff.

^ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture.

Blackwell Publishing. pp. 102. ISBN 1-4051-0316-7.

^ a b c Beekes, Robert S. P. (1995). Comparative Indo-European

Linguistics: An Introduction. ISBN 1-55619-505-1.

^ Buck, Carl Darling (1933). Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-07931-7.

^ Sihler, Andrew L. (1995). New Comparative Grammar of Greek and

Latin. Oxford University Press. pp. 402–24. ISBN 0-19-508345-8.

^ Lehmann, Winfried P. (1993). Theoretical Bases of Indo-European

Linguistics. London: Routledge. pp. 252–255. ISBN 0-415-08201-3.

See also

Look up Appendix:List of Proto-Indo-European roots in Wiktionary, the

free dictionary.

http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:List_of_Proto-Indo-European_roots

Indo-European languages http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_languages

Laryngeal theory http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laryngeal_theory

List of Indo-European languages http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Indo-European_languages

Daughter proto-languages

Proto-Armenian language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Armenian_language

Proto-Balto-Slavic language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Balto-Slavic_language

Proto-Celtic language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Celtic_language

Proto-Germanic language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Germanic_language

Proto-Greek language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Greek_language

Proto-Indo-Iranian language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-Iranian_language

Proto-Italic language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:WhatLinksHere/Proto-Italic_language

References

Beekes, Robert S. P. (1995). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An

Introduction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 90-272-2150-2 (Europe),

ISBN 1-55619-504-4 (U.S.).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_S._P._Beekes

James Clackson (2007). Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction

(Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics). Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. ISBN 0-52165-313-4.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Clackson

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambridge_University_Press

Buck, Carl Darling (1933). Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-07931-7.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Darling_Buck

Lehmann, W., and L. Zgusta. 1979. Schleicher's tale after a century.

In Festschrift for Oswald Szemerényi on the Occasion of his 65th

Birthday, ed. B. Brogyanyi, 455–66. Amsterdam.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winfred_P._Lehmann

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zgusta

Mallory, J.P., (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans London: Thames

and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1

Mayrhofer, Manfred (1986). Indogermanische Grammatik, i/2: Lautlehre.

Heidelberg: Winter.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manfred_Mayrhofer

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heidelberg

Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (2006), The Oxford Introduction to Proto-

Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, Oxford: Oxford

University Press, ISBN 0199296682

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J.P._Mallory

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Q._Adams

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxford_University_Press

Meier-Brügger, Michael (2003). Indo-European Linguistics. New York: de

Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017433-2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meier-Br%C3%BCgger

Renfrew, Colin (1987). Archaeology & Language. The Puzzle of the Indo-

European Origins. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-02495-7

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colin_Renfrew

Sihler, Andrew L. (1995). New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin.

Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508345-8.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Sihler

Szemerényi, Oswald (1996). Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics.

Oxford. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oswald_Szemer%C3%A9nyi

Vyacheslav V. Ivanov and Thomas Gamkrelidze, The Early History of Indo-

European Languages, Scientific American, vol. 262, N3, 110116, March,

1990

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vyacheslav_Vsevolodovich_Ivanov

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Gamkrelidze

Whitney, William Dwight (1889). Sanskrit Grammar. Harvard University

Press. ISBN 81-208-0621-2 (India), ISBN 0-486-43136-3 (Dover, US).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Dwight_Whitney

Remys, Edmund, General distinguishing features of various Indo-

European languages and their relationship to Lithuanian,

Indogermanische Forschungen, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York, Band

112, 2007.

External links

Indo-European Dictionary by Gerhard Köbler (contains Indo-European

Grammar in Vorwort section) (German) http://www.koeblergerhard.de/idgwbhin.html

A list of PIE etyma and their meanings from the Indo-European

Etymological Dictionary by Julius Pokorny (University of Texas)

http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/ielex/PokornyMaster-X.html

Database query for Pokorny's dictionary (includes comments and

searchable cognates) (Leiden University)

http://www.ieed.nl/cgi-bin/startq.cgi?flags=endnnnl&root=leiden&basename=%5Cdata%5Cie%5Cpokorny

Comparative Notes on Hurro-Urartian, Northern Caucasian and Indo-

European (by Vyacheslav V. Ivanov) http://www.humnet.ucla.edu/pies/pdfs/IESV/1/VVI_Horse.pdf

Indo-European family tree, showing Indo-European languages and sub

branches Loading Image...

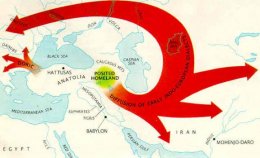

Image of Indo-European migrations from the Armenian Highlands

Loading Image...

PIE theoretical grammar http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/books/pies01.html

Indo-European Etymological Dictionary database (Leiden University)

http://www.ieed.nl/

Indo-European Documentation Center at the University of Texas

http://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/lrc/iedocctr/ie.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Texas_at_Austin

"The Indo-Uralic Verb" by Frederik Kortlandt

http://www.kortlandt.nl/publications/art203e.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederik_Kortlandt

Say something in Proto-Indo-European (by Geoffrey Sampson)

http://www.grsampson.net/Q_PIE.html

An Overview of the Proto-Indo-European Verb System (by Piotr

Gąsiorowski)

Many PIE example texts http://verger1.narod.ru/lang1.htm/

PIE root etymology database (by S.L.Nikolaev and S.A.Starostin)

http://starling.rinet.ru/cgi-bin/response.cgi?root=config&morpho=0&basename=\data\ie\piet&first=1

On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey by

Václav Blažek. Linguistica ONLINE. ISSN 1801-5336 (Brno, Czech

Republic)

http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V%C3%A1clav_Bla%C5%BEek

http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brno

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Czech_Republic

v • d • e

Proto-Indo-European language

Phonology . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_phonology

Accent · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_accent

Glottalic theory · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glottalic_theory

Laryngeal theory · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laryngeal_theory

s-mobile · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_s-mobile

Sound laws http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_sound_laws

(Bartholomae's, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartholomae%27s_law

kʷetwóres rule, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%CA%B7etw%C3%B3res_rule

Pinault's, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinault%27s_law

Siebs', http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siebs%27_law

Sievers', http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sievers%27_law

Stang's, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stang%27s_law

Szemerényi's), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Szemer%C3%A9nyi%27s_law

Morphology

Ablaut · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_ablaut

h₂e-conjugation · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H%E2%82%82e-conjugation_theory

Nasal infix · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nasal_infix

Root · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_root

Thematic/athematic stem . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thematic_stem

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athematic_stem

Parts of speech

Noun · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_noun

Numeral · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_numerals

Particle · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_particle

Pronoun · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_pronoun

Verb . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_verb

(copula) . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_copula

See also:

Proto-Indo-European religion · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_religion

Proto-Indo-European society · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_society

Indo-European studies . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_studies

Categories:

Proto-Indo-European language | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Proto-Indo-European_language

Indo-European | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Indo-European

Proto-languages | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Proto-languages

Bronze Age | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Bronze_Age

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_language

http://bakulaji.typepad.com/blog/protoindoeuropean-language-sid-harth.html

...and I am Sid Harth

Proto-Indo-European language

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"PIE" redirects here. For the pastry, see Pie. For other uses, see PIE

(disambiguation).

This article contains characters used to write reconstructed Proto-

Indo-European words. Without proper rendering support, you may see

question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode

characters.

Indo-European topics

Indo-European languages (list) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_languages

Albanian · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albanian_language

Armenian · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armenian_language

Baltic . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baltic_languages

Celtic · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celtic_languages

Germanic · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germanic_languages

Greek . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_language

Indo-Iranian . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Iranian_languages

(Indo-Aryan, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Aryan_languages

Iranian) . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iranian_languages

Italic · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italic_languages

Slavic . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavic_languages

extinct:

Anatolian · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatolian_languages

Paleo-Balkans http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paleo-Balkan_languages

(Dacian, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dacian_language

Phrygian, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phrygian_language

Thracian) · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thracian_language

Tocharian . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tocharian_languages

Indo-European peoples http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_people

Europe:

Balts · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balts

Slavs · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavic_peoples

Albanians · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albanians

Italics · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_peoples_of_Italy

Celts · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celts

Germanic peoples · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germanic_peoples

Greeks · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greeks

Paleo-Balkans

(Illyrians · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illyrians

Thracians · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thracians

Dacians) · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dacians

Asia:

Anatolians . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatolians

(Hittites, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hittites

Luwians) · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luwians

Armenians · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armenians

Indo-Iranians . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Iranians

(Iranians· http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iranian_peoples

Indo-Aryans) · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Aryans

Tocharians . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tocharians

Proto-Indo-Europeans http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-Europeans

Language · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_language

Society · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_society

Religion . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_religion

Urheimat hypotheses http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_Urheimat_hypotheses

Kurgan hypothesis http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurgan_hypothesis

Anatolia · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatolian_hypothesis

Armenia · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armenian_hypothesis

India · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Out_of_India_theory

PCT . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paleolithic_Continuity_Theory

Indo-European studies http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_studies

The Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) is the unattested,

reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, spoken

by the Proto-Indo-Europeans. The existence of such a language has been

accepted by linguists for over a century, and reconstruction is far

advanced and quite detailed.

Scholars estimate that PIE may have been spoken as a single language

(before divergence began) around 4000 BC, though estimates by

different authorities can vary by more than a millennium. The most

popular hypothesis for the origin and spread of the language is the

Kurgan hypothesis, which postulates an origin in the Pontic-Caspian

steppe of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. In modern times the

existence of the language was first postulated in the 18th century by

Sir William Jones, who observed the similarities between Sanskrit,

Ancient Greek, and Latin. By the early 1900s well-defined descriptions

of PIE had been developed that are still accepted today (with some

refinements).

As there is no direct evidence of Proto-Indo-European language, all

knowledge of the language is derived by reconstruction from later

languages using linguistic techniques such as the comparative method

and the method of internal reconstruction. PIE is known to have had a

complex system of morphology that included inflections (adding

prefixes and suffixes to word roots, as is common in Romance

languages), and ablaut (changing vowel sounds in word roots, as is

common in Germanic languages). Nouns used a sophisticated system of

declension and verbs used a similarly sophisticated system of

conjugation.

Relationships to other language families, including the Uralic

languages, have been proposed though all such suggestions remain

controversial.

Discovery and reconstruction

Classification of Indo-European languages. (click to enlarge)

Historical and geographical setting

Main article: Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_Urheimat_hypotheses

There are several competing hypotheses about when and where PIE was

spoken. The Kurgan hypothesis is "the single most popular" model,[1]

[2] postulating that the Kurgan culture of the Pontic steppe were the

hypothesized speakers of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European

language. However, alternative theories such as the Anatolian urheimat

and Armenian hypothesis have also gained acceptance.

The satemization process that resulted in the Centum-Satem isogloss

probably started as early as the fourth millennium BC[3] and the only

thing known for certain is that the proto language must have been

differentiated into unconnected daughter dialects by the late 3rd

millennium BC.

Mainstream linguistic estimates of the time between PIE and the

earliest attested texts (ca. nineteenth century BC; see Kültepe texts)

range around 1,500 to 2,500 years, with extreme proposals diverging up

to another 100% on either side. Other than the aforementioned,

predominant Kurgan hypothesis, proposed models include:

the 4th millennium BC (excluding the Anatolian branch) in Armenia,

according to the Armenian hypothesis (proposed in the context of

Glottalic theory);

the 5th millennium BC (4th excluding the Anatolian branch) in the

Pontic-Caspian steppe, according to the popular Kurgan hypothesis;

the 6th millennium BC or later in Northern Europe according to Lothar

Kilian's and, especially, Marek Zvelebil's models of a broader

homeland;

the 6th millennium BC in India, according to Koenraad Elst's Out of

India model;

the 7th millennium BC in Ariana/BMAC according to a number of

scholars.

the 7th millennium BC in Anatolia (the 5th, in the Balkans, excluding

the Anatolian branch), according to Colin Renfrew's Anatolian

hypothesis;

the 7th millennium BC in Anatolia (6th excluding the Anatolian

branch), according to a 2003 glottochronological study;[4]

before the 10th millennium BC, in the Paleolithic Continuity Theory.

History

Main article: Indo-European studies http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_studies

Indo-European studies began with Sir William Jones making and

propagating the observation that Sanskrit bore a certain resemblance

to classical Greek and Latin. In The Sanscrit Language (1786) he

suggested that all three languages had a common root, and that indeed

they may all be further related, in turn, to Gothic and the Celtic

languages, as well as to Persian.

His third annual discourse before the Asiatic Society on the history

and culture of the Hindus (delivered on 2 February 1786 and published

in 1788) with the famed "philologer" passage is often cited as the

beginning of comparative linguistics and Indo-European studies. This

is Jones' most quoted passage, establishing his tremendous find in the

history of linguistics:

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful

structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin,

and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them

a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of

grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong

indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without

believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps,

no longer exists; there is a similar reason, though not quite so

forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though

blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the

Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family.

This common source came to be known as Proto-Indo-European.

The classical phase of Indo-European comparative linguistics leads

from Franz Bopp's Comparative Grammar (1833) to August Schleicher's

1861 Compendium and up to Karl Brugmann's Grundriss published from the

1880s. Brugmann's junggrammatische re-evaluation of the field and

Ferdinand de Saussure's development of the laryngeal theory may be

considered the beginning of "contemporary" Indo-European studies.

PIE as described in the early 1900s is still generally accepted today;

subsequent work is largely refinement and systematization, as well as

the incorporation of new information, notably the Anatolian and

Tocharian branches unknown in the 19th century.

Notably, the laryngeal theory, in its early forms discussed since the

1880s, became mainstream after Jerzy Kuryłowicz's 1927 discovery of

the survival of at least some of these hypothetical phonemes in

Anatolian. Julius Pokorny's Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

(1959) gave an overview of the lexical knowledge accumulated until the

early 20th century, but neglected contemporary trends of morphology

and phonology, and largely ignored Anatolian and Tocharian.

The generation of Indo-Europeanists active in the last third of the

20th century (such as Calvert Watkins, Jochem Schindler and Helmut

Rix) developed a better understanding of morphology and, in the wake

of Kuryłowicz's 1956 Apophonie, understanding of the ablaut. From the

1960s, knowledge of Anatolian became certain enough to establish its

relationship to PIE; see also Indo-Hittite.

Method

Main articles: Historical linguistics and Indo-European sound laws

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_linguistics

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_sound_laws

There is no direct evidence of PIE, because it was never written. All

PIE sounds and words are reconstructed from later Indo-European

languages using the comparative method and the method of internal

reconstruction. An asterisk is used to mark reconstructed PIE words,

such as *wódr̥ 'water', *ḱwṓn 'dog' (English hound), or *tréyes 'three

(masculine)'. Many of the words in the modern Indo-European languages

seem to have derived from such "protowords" via regular sound changes

(e.g., Grimm's law).

As the Proto-Indo-European language broke up, its sound system

diverged as well, according to various sound laws in the daughter

languages. Notable among these are Grimm's law and Verner's law in

Proto-Germanic, loss of prevocalic *p- in Proto-Celtic, reduction to h

of prevocalic *s- in Proto-Greek, Brugmann's law and Bartholomae's law

in Proto-Indo-Iranian, Grassmann's law independently in both Proto-

Greek and Proto-Indo-Iranian, and Winter's law and Hirt's law in Balto-

Slavic.

Relationships to other language families

Proposed genetic connections

Many higher-level relationships between Proto-Indo-European and other

language families have been proposed, but these hypothesized

connections are highly controversial. A proposal often considered to

be the most plausible of these is that of an Indo-Uralic family,

encompassing PIE and Uralic. The evidence usually cited in favor of

this consists in a number of striking morphological and lexical

resemblances. Opponents attribute the lexical resemblances to

borrowing from Indo-European into Uralic. Frederik Kortlandt, while

advocating a connection, concedes that "the gap between Uralic and

Indo-European is huge", while Lyle Campbell, an authority on Uralic,

denies any relationship exists.

Other proposals, further back in time (and proportionately less

accepted), link Indo-European and Uralic with Altaic and the other

language families of northern Eurasia, namely Yukaghir, Korean,

Japanese, Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Nivkh, Ainu, and Eskimo-Aleut, but

excluding Yeniseian (the most comprehensive such proposal is Joseph

Greenberg's Eurasiatic), or link Indo-European, Uralic, and Altaic to

Afro-Asiatic and Dravidian (the traditional form of the Nostratic

hypothesis), and ultimately to a single Proto-Human family.

A more rarely mentioned proposal associates Indo-European with the

Northwest Caucasian languages in a family called Proto-Pontic.

Etruscan shows some similarities to Indo-European. There is no

consensus on whether these are due to a genetic relationship,

borrowing, chance and sound symbolism, or some combination of these.

Proposed areal connections

The existence of certain PIE typological features in Northwest

Caucasian languages may hint at an early Sprachbund[5] or substratum

that reached geographically to the PIE homelands.[6] This same type of

languages, featuring complex verbs and of which the current Northwest

Caucasian languages might have been the sole survivors, was cited by

Peter Schrijver to indicate a local lexical and typological

reminiscence in western Europe pointing to a possible Neolithic

substratum.[7]

Phonology

Main article: Proto-Indo-European phonology

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_phonology

Consonants

Labial Coronal Dorsal Laryngeal

palatal plain labial

Nasal *m *n

Plosive voiceless

*p *t *ḱ *k *kʷ

voiced *b *d *ǵ *g *gʷ

aspirated *bʰ *dʰ *ǵʰ *gʰ *gʷʰ

Fricative *s *h₁, *h₂, *h₃

Liquid *r, *l

Semivowel *y *w

Alternative notations: The aspirated plosives are sometimes written as

*bh, *dh, *ǵh, *gh, *gʷh; for the palatals, *k̑, *g̑ are often used;

and *i̯, *u̯ can replace *y, *w.

The pronunciation of the laryngeals is disputed, at least *h₁ might

not have been a fricative.

Vowels

Short vowels: *e, *o (and possibly *a).

Long vowels: *ē, *ō (and possibly *ā). Sometimes a colon (:) is

employed instead of the macron sign to indicate vowel length (*a:,

*e:, *o:).

Diphthongs: *ei, *eu, *ēi, *ēu, *oi, *ou, *ōi, *ōu, (*ai, *au, *āi,

*āu). Diphthongs are sometimes understood as combinations of a vowel

plus a semivowel, e. g. *ey or *ei̯ instead of *ei.[8]

Vocalic allophones of laryngeals, nasals, liquids and semivowels:

*h̥₁, *h̥₂, *h̥₃, *m̥, *n̥, *l̥, *r̥, *i, *u.

Long variants of these vocalic allophones may have appeared already in

the proto-language by compensatory lengthening (for example of a vowel

plus a laryngeal): *m̥̄, *n̥̄, *l̥̄, *r̥̄, *ī, *ū.

It is often suggested that all *a and *ā were earlier derived from an

*e preceded or followed by *h₂, but Mayrhofer[9] has argued that PIE

did in fact have *a and *ā phonemes independent of h₂.

Morphology

Root

Main article: Proto-Indo-European root http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_root

PIE was an inflected language, in which the grammatical relationships

between words were signaled through inflectional morphemes (usually

endings). The roots of PIE are basic morphemes carrying a lexical

meaning. By addition of suffixes, they form stems, and by addition of

desinences (usually endings), these form grammatically inflected words

(nouns or verbs). PIE roots are understood to be predominantly

monosyllabic with a basic shape CvC(C). This basic root shape is often

altered by ablaut. Roots which appear to be vowel initial are believed

by many scholars to have originally begun with a set of consonants,

later lost in all but the Anatolian branch, called laryngeals (usually

indicated *H, and often specified with a subscript number *h₁, *h₂,

*h₃). Thus a verb form such as the one reflected in Latin agunt, Greek

ἄγουσι (ágousi), Sanskrit ajanti would be reconstructed as *h₂eǵ-onti,

with the element *h₂eǵ- constituting the root per se.

Ablaut

Main article: Indo-European ablaut http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_ablaut

One of the distinctive aspects of PIE was its ablaut sequence that

contrasted the vowel phonemes *o / *e / Ø [no vowel] within the same

root. Ablaut is a form of vowel variation which changed between these

three forms perhaps depending on the adjacent sounds and placement of

stress in the word. These changes are echoed in modern Indo-European

languages where they have come to reflect grammatical categories.

These ablaut grades are usually referred to as: e-grade and o-grade,

sometimes collectively termed full grade; zero-grade (no vowel, Ø);

and lengthened grade (*ē or *ō). Modern English sing, sang, sung is an

example of such an ablaut set and reflects a pre-Proto-Germanic

sequence *sengw-, *songw-, *sngw-. Some scholars believe that the

inflectional affixes of Indo European reflect ablaut variants, usually

zero-grade, of older PIE roots. Often the zero-grade appears where the

word's accent has shifted from the root to one of the affixes. Thus

the alternation found in Latin est, sunt reflects PIE *h₁és-ti, *h₁s-

ónti.

Noun

Main article: Proto-Indo-European noun http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_noun

Proto-Indo-European nouns were declined for eight or nine cases

(nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental, ablative,

locative, vocative, and possibly a directive or allative).[10] There

were three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter.

There are two major types of declension, thematic and athematic.

Thematic nominal stems are formed with a suffix *-o- (in vocative *-e)

and the stem does not undergo ablaut. The athematic stems are more

archaic, and they are classified further by their ablaut behaviour

(acro-dynamic, protero-dynamic, hystero-dynamic and holo-dynamic,

after the positioning of the early PIE accent (dynamis) in the

paradigm).

Pronoun

Main article: Proto-Indo-European pronoun http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_pronoun

PIE pronouns are difficult to reconstruct owing to their variety in

later languages. This is especially the case for demonstrative

pronouns. PIE had personal pronouns in the first and second person,

but not the third person, where demonstratives were used instead. The

personal pronouns had their own unique forms and endings, and some had

two distinct stems; this is most obvious in the first person singular,

where the two stems are still preserved in English I and me. According

to Beekes,[11] there were also two varieties for the accusative,

genitive and dative cases, a stressed and an enclitic form.

Personal pronouns (Beekes)

First person Second person

Singular Plural Singular Plural

Nominative *h₁eǵ(oH/Hom) *wei *tuH *yuH

Accusative *h₁mé, *h₁me *nsmé, *nōs *twé *usmé, *wōs

Genitive *h₁méne, *h₁moi *ns(er)o-, *nos *tewe, *toi *yus(er)o-, *wos

Dative *h₁méǵʰio, *h₁moi *nsmei, *ns *tébʰio, *toi *usmei

Instrumental *h₁moí ? *toí ?

Ablative *h₁med *nsmed *tued *usmed

Locative *h₁moí *nsmi *toí *usmi

As for demonstratives, Beekes tentatively reconstructs a system with

only two pronouns: *so / *seh₂ / *tod "this, that" and *h₁e /

*(h₁)ih₂ / *(h₁)id "the (just named)" (anaphoric). He also postulates

three adverbial particles *ḱi "here", *h₂en "there" and *h₂eu "away,

again", from which demonstratives were constructed in various later

languages.

Verb

Main article: Proto-Indo-European verb http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_verb

The Indo-European verb system is complex and, like the noun, exhibits

a system of ablaut. Verbs have at least four moods (indicative,

imperative, subjunctive and optative, as well as possibly the

injunctive, reconstructible from Vedic Sanskrit), two voices (active

and mediopassive), as well as three persons (first, second and third)

and three numbers (singular, dual and plural). Verbs are conjugated in

at least three "tenses" (present, aorist, and perfect), which actually

have primarily aspectual value. Indicative forms of the imperfect and

(less likely) the pluperfect may have existed. Verbs were also marked

by a highly developed system of participles, one for each combination

of tense and mood, and an assorted array of verbal nouns and

adjectival formations.

Buck[12] Beekes[11]

Athematic Thematic Athematic Thematic

Singular 1st *-mi *-ō *-mi *-oH

2nd *-si *-esi *-si *-eh₁i

3rd *-ti *-eti *-ti *-e

Plural 1st *-mos/mes *-omos/omes *-mes *-omom

2nd *-te *-ete *-th₁e *-eth₁e

3rd *-nti *-onti *-nti *-o

Numbers

Main article: Proto-Indo-European numerals

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_numerals

The Proto-Indo-European numerals are generally reconstructed as

follows:

Sihler[13] Beekes[11]

one *Hoi-no-/*Hoi-wo-/*Hoi-k(ʷ)o-; *sem- *Hoi(H)nos

two *d(u)wo- *duoh₁

three *trei- (full grade) / *tri- (zero grade) *treies

four *kʷetwor- (o-grade) / *kʷetur- (zero grade)

(see also the kʷetwóres rule) *kʷetuōr

five *penkʷe *penkʷe

six *s(w)eḱs; originally perhaps *weḱs *(s)uéks

seven *septm̥ *séptm

eight *oḱtō, *oḱtou or *h₃eḱtō, *h₃eḱtou *h₃eḱteh₃

nine *(h₁)newn̥ *(h₁)néun

ten *deḱm̥(t) *déḱmt

twenty *wīḱm̥t-; originally perhaps *widḱomt- *duidḱmti

thirty *trīḱomt-; originally perhaps *tridḱomt- *trih₂dḱomth₂

forty *kʷetwr̥̄ḱomt-; originally perhaps *kʷetwr̥dḱomt-

*kʷeturdḱomth₂

fifty *penkʷēḱomt-; originally perhaps *penkʷedḱomt- *penkʷedḱomth₂

sixty *s(w)eḱsḱomt-; originally perhaps *weḱsdḱomt- *ueksdḱomth₂

seventy *septm̥̄ḱomt-; originally perhaps *septm̥dḱomt- *septmdḱomth₂

eighty *oḱtō(u)ḱomt-; originally perhaps *h₃eḱto(u)dḱomt-

*h₃eḱth₃dḱomth₂

ninety *(h₁)newn̥̄ḱomt-; originally perhaps *h₁newn̥dḱomt-

*h₁neundḱomth₂

hundred *ḱm̥tom; originally perhaps *dḱm̥tom *dḱmtóm

thousand *ǵheslo-; *tusdḱomti *ǵʰes-l-

Lehmann[14] believes that the numbers greater than ten were

constructed separately in the dialects groups and that *ḱm̥tóm

originally meant "a large number" rather than specifically "one

hundred."

Particle

Main article: Proto-Indo-European particlehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_particle

Many particles could be used both as adverbs and postpositions, like

*upo "under, below". The postpositions became prepositions in most

daughter languages. Other reconstructible particles include negators

(*ne, *mē), conjunctions (*kʷe "and", *wē "or" and others) and an

interjection (*wai!, an expression of woe or agony).

Sample texts

As PIE was spoken by a prehistoric society, no genuine sample texts

are available, but since the 19th century modern scholars have made

various attempts to compose example texts for purposes of

illustration. These texts are educated guesses at best; Calvert

Watkins in 1969 observes that in spite of its 150 years' history,

comparative linguistics is not in the position to reconstruct a single

well-formed sentence in PIE. Nevertheless, such texts do have the

merit of giving an impression of what a coherent utterance in PIE

might have sounded like.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calvert_Watkins

Published PIE sample texts:

Schleicher's fable (Avis akvasas ka) by August Schleicher (1868),

modernized by Hermann Hirt (1939) and Winfred Lehmann and Ladislav

Zgusta (1979)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schleicher%27s_fable

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/August_Schleicher

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann_Hirt

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winfred_Lehmann

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ladislav_Zgusta

The king and the god (rēḱs deiwos-kʷe) by S. K. Sen, E. P. Hamp et al.

(1994)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_king_and_the_god

Notes

^ Mallory (1989:185). "The Kurgan solution is attractive and has been

accepted by many archaeologists and linguists, in part or total. It is

the solution one encounters in the Encyclopaedia Britannica and the

Grand Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Larousse."

^ Strazny (2000:163). "The single most popular proposal is the Pontic

steppes (see the Kurgan hypothesis)..."

^ ".. the satemization process can be dated to the last centuries of

the fourth millennium." [1] THE SPREAD OF THE INDO-EUROPEANS -Frederik

Kortlandt.

^ Russell D. Gray and Quentin D. Atkinson, Language-tree divergence

times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin, Nature 426

(27 November 2003) 435-439

^ [2] Frederik Kortlandt-GENERAL LINGUISTICS AND INDO-EUROPEAN

RECONSTRUCTION, 1993

^ [3] The spread of the Indo-Europeans - Frederik Kortlandt, 1989

^ [4] Peter Schrijver - Keltisch en de buren: 9000 jaar taalcontact,

University of Utrecht, March 2007.

^ Rix, H. Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben (2 ed.).

^ Mayrhofer 1986: 170 ff.

^ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture.

Blackwell Publishing. pp. 102. ISBN 1-4051-0316-7.

^ a b c Beekes, Robert S. P. (1995). Comparative Indo-European

Linguistics: An Introduction. ISBN 1-55619-505-1.

^ Buck, Carl Darling (1933). Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-07931-7.

^ Sihler, Andrew L. (1995). New Comparative Grammar of Greek and

Latin. Oxford University Press. pp. 402–24. ISBN 0-19-508345-8.

^ Lehmann, Winfried P. (1993). Theoretical Bases of Indo-European

Linguistics. London: Routledge. pp. 252–255. ISBN 0-415-08201-3.

See also

Look up Appendix:List of Proto-Indo-European roots in Wiktionary, the

free dictionary.

http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:List_of_Proto-Indo-European_roots

Indo-European languages http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_languages

Laryngeal theory http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laryngeal_theory

List of Indo-European languages http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Indo-European_languages

Daughter proto-languages

Proto-Armenian language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Armenian_language

Proto-Balto-Slavic language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Balto-Slavic_language

Proto-Celtic language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Celtic_language

Proto-Germanic language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Germanic_language

Proto-Greek language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Greek_language

Proto-Indo-Iranian language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-Iranian_language

Proto-Italic language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:WhatLinksHere/Proto-Italic_language

References

Beekes, Robert S. P. (1995). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An

Introduction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 90-272-2150-2 (Europe),

ISBN 1-55619-504-4 (U.S.).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_S._P._Beekes

James Clackson (2007). Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction

(Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics). Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. ISBN 0-52165-313-4.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Clackson

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambridge_University_Press

Buck, Carl Darling (1933). Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-07931-7.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Darling_Buck

Lehmann, W., and L. Zgusta. 1979. Schleicher's tale after a century.

In Festschrift for Oswald Szemerényi on the Occasion of his 65th

Birthday, ed. B. Brogyanyi, 455–66. Amsterdam.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winfred_P._Lehmann

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zgusta

Mallory, J.P., (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans London: Thames

and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1

Mayrhofer, Manfred (1986). Indogermanische Grammatik, i/2: Lautlehre.

Heidelberg: Winter.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manfred_Mayrhofer

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heidelberg

Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (2006), The Oxford Introduction to Proto-

Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, Oxford: Oxford

University Press, ISBN 0199296682

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J.P._Mallory

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Q._Adams

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxford_University_Press

Meier-Brügger, Michael (2003). Indo-European Linguistics. New York: de

Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017433-2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meier-Br%C3%BCgger

Renfrew, Colin (1987). Archaeology & Language. The Puzzle of the Indo-

European Origins. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-02495-7

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colin_Renfrew

Sihler, Andrew L. (1995). New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin.

Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508345-8.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Sihler

Szemerényi, Oswald (1996). Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics.

Oxford. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oswald_Szemer%C3%A9nyi

Vyacheslav V. Ivanov and Thomas Gamkrelidze, The Early History of Indo-

European Languages, Scientific American, vol. 262, N3, 110116, March,

1990

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vyacheslav_Vsevolodovich_Ivanov

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Gamkrelidze

Whitney, William Dwight (1889). Sanskrit Grammar. Harvard University

Press. ISBN 81-208-0621-2 (India), ISBN 0-486-43136-3 (Dover, US).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Dwight_Whitney

Remys, Edmund, General distinguishing features of various Indo-

European languages and their relationship to Lithuanian,

Indogermanische Forschungen, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York, Band

112, 2007.

External links

Indo-European Dictionary by Gerhard Köbler (contains Indo-European

Grammar in Vorwort section) (German) http://www.koeblergerhard.de/idgwbhin.html

A list of PIE etyma and their meanings from the Indo-European

Etymological Dictionary by Julius Pokorny (University of Texas)

http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/ielex/PokornyMaster-X.html

Database query for Pokorny's dictionary (includes comments and

searchable cognates) (Leiden University)

http://www.ieed.nl/cgi-bin/startq.cgi?flags=endnnnl&root=leiden&basename=%5Cdata%5Cie%5Cpokorny

Comparative Notes on Hurro-Urartian, Northern Caucasian and Indo-

European (by Vyacheslav V. Ivanov) http://www.humnet.ucla.edu/pies/pdfs/IESV/1/VVI_Horse.pdf

Indo-European family tree, showing Indo-European languages and sub

branches Loading Image...

Image of Indo-European migrations from the Armenian Highlands

Loading Image...

PIE theoretical grammar http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/books/pies01.html

Indo-European Etymological Dictionary database (Leiden University)

http://www.ieed.nl/

Indo-European Documentation Center at the University of Texas

http://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/lrc/iedocctr/ie.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Texas_at_Austin

"The Indo-Uralic Verb" by Frederik Kortlandt

http://www.kortlandt.nl/publications/art203e.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederik_Kortlandt

Say something in Proto-Indo-European (by Geoffrey Sampson)

http://www.grsampson.net/Q_PIE.html

An Overview of the Proto-Indo-European Verb System (by Piotr

Gąsiorowski)

Many PIE example texts http://verger1.narod.ru/lang1.htm/

PIE root etymology database (by S.L.Nikolaev and S.A.Starostin)

http://starling.rinet.ru/cgi-bin/response.cgi?root=config&morpho=0&basename=\data\ie\piet&first=1

On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey by

Václav Blažek. Linguistica ONLINE. ISSN 1801-5336 (Brno, Czech

Republic)

http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V%C3%A1clav_Bla%C5%BEek

http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brno

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Czech_Republic

v • d • e

Proto-Indo-European language

Phonology . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_phonology

Accent · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_accent

Glottalic theory · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glottalic_theory

Laryngeal theory · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laryngeal_theory

s-mobile · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_s-mobile

Sound laws http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_sound_laws

(Bartholomae's, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartholomae%27s_law

kʷetwóres rule, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%CA%B7etw%C3%B3res_rule

Pinault's, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinault%27s_law

Siebs', http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siebs%27_law

Sievers', http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sievers%27_law

Stang's, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stang%27s_law

Szemerényi's), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Szemer%C3%A9nyi%27s_law

Morphology

Ablaut · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_ablaut

h₂e-conjugation · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H%E2%82%82e-conjugation_theory

Nasal infix · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nasal_infix

Root · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_root

Thematic/athematic stem . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thematic_stem

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athematic_stem

Parts of speech

Noun · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_noun

Numeral · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_numerals

Particle · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_particle

Pronoun · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_pronoun

Verb . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_verb

(copula) . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_copula

See also:

Proto-Indo-European religion · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_religion

Proto-Indo-European society · http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_society

Indo-European studies . http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_studies

Categories:

Proto-Indo-European language | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Proto-Indo-European_language

Indo-European | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Indo-European

Proto-languages | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Proto-languages

Bronze Age | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Bronze_Age

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_language

http://bakulaji.typepad.com/blog/protoindoeuropean-language-sid-harth.html

...and I am Sid Harth